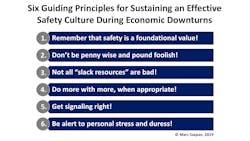

Six Guiding Principles for Sustaining an Effective Safety Culture During Economic Downturns

Building and maintaining an effective safety culture is no easy feat in the best of times. Doing so during an economic downturn tends to be an even more challenging endeavor, even for the best-run businesses. This article suggests six guiding principles for sustaining an effective safety culture during tough economic times.

Clouds on the Horizon

Historically, the aviation industry has been characterized by boom-and-bust cycles. Fortunately, it is currently enjoying one of its longest growth phases. For example, the International Air Transport Association (IATA) forecasts that this year will be the 10th consecutive year of positive earnings for the airline industry. However, there are clouds on the horizon. In terms of global macro-economic performance, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has warned of a synchronized slowdown across major economies of the world. Closer to home, there are a number of aviation industry-specific forward indicators, such as slowing demand and peaking aircraft orders that point to the risk of a looming downturn.

Sustaining an Effective Safety Culture

In light of these general macro-economic and industry-specific risks, aviation businesses would be well advised to prepare for a potential economic downturn. Leaders of aviation businesses need to ensure that the safety culture at the heart of any high caliber aviation operation will not fall victim to the realities of exacerbated financial and operational pressures that invariably come hand-in-hand with economic downturns. This article suggests six principles that can guide aviation leaders — and those of other safety-critical businesses for that matter — in their quest to protect an organization’s safety culture when having to make difficult trade-off and cost-management decisions.

1. Remember that safety is a foundational value. In any organization, there are certain foundational values that define what the organization is all about. These defining values should be non-negotiable and should not be driven by financial cost-benefit calculations. For example, in the military, never leaving a buddy behind on the field of battle is a foundational value that is at the heart of the identity of any soldier and of unit cohesion. In aviation, the commitment to the safety of passengers, employees, suppliers and communities in which one operates is a defining value and part of the DNA of any respectable aviation business and aviation professional. This foundational commitment to safety should not be subject to purported cost-benefit, return-on-investment or business case considerations, especially in the context of cost-cutting initiatives during economic downturns.

2. Don’t be penny wise and pound foolish. As stated above, the commitment to safety should be part of the DNA of any aviation business. As a foundational value, it should be non-negotiable and not fall victim to considerations of financial optimization. At the same time, it is worthwhile to remember the old adage “If you think safety is expensive, try an accident”. Often, investments into a positive safety culture and the corresponding technical, organizational and human resources are relatively minor. Usually, they are much lower than the direct and indirect costs — moral, reputational, financial and otherwise — of serious incidents, let alone accidents involving loss of human life that can result in the need to re-design products that had been brought to market prematurely without sufficient consideration of safety-relevant details.

3. Not all “slack resources” are bad. When assessing cost-cutting opportunities, aviation leaders ought to stay clear of “penny wise and pound foolish” traps and pursue sustainable cost-management strategies. One of the most straightforward and therefore most tempting approaches to cost-cutting is getting rid of “slack resources”. However, before enthusiastically cutting the apparent excess of a particular resource, aviation businesses should keep in mind that appropriately calibrated “slack resources” can enhance organizational resilience and allow to buffer shocks. As much as one would not operate a flight without any alternate or contingency fuel, “slack resources” can provide the extra margin that allows an organization to get safely through a crisis or unforeseen circumstances. In the end, the merit of not minimizing fuel reserves to zero and not reducing resources to the point of incurring single failure modes should be obvious for any aviation professional.

4. Do more with more, when appropriate. In the context of navigating safety management challenges during an economic downturn, protecting “slack resources” can be a necessary, but by no means sufficient, approach to cost management. Adding to one’s cost basis during a downturn certainly seems counter intuitive. However, in the case of quality and safety management functions, adding rather than maintaining — let alone reducing — resources can be a recommended course of action. After all, tighter financial and operational constraints during a downturn can exacerbate organizational stresses. It should be no surprise that regulatory authorities often intensify their monitoring of aviation businesses exactly during these times. Doing adequate justice to internal organizational dynamics and stresses and to intensified regulatory supervision can generate significantly higher workloads in the areas of quality and safety management. Aviation businesses might be well-advised to increase resourcing of these critical functions during times of cost-cutting pressures.

5. Get signaling right. Credible commitment to a positive safety culture is as much a function of adequate resourcing as of effective signaling on the part of a business’ leadership team, vis-à-vis its workforce. Getting this right in ordinary circumstances is not a trivial undertaking in the first place (see my article “Four Ways to Champion a Positive Safety and Quality Culture” in the Aircraft Maintenance Technology June/July 2018 issue). In tough economic circumstances characterized by difficult and often painful trade-off decisions, effective signaling becomes even more important. One of the easiest ways of negative signaling with respect to the importance of safety is an undifferentiated approach to cost management. Across-the-board cost-cutting such as a 10 percent reduction of all budget line items regardless of implications for safety above and beyond the direct budgets for quality and safety management functions fails to signal priorities such as protecting an organization’s safety culture. It is likely to send the wrong message.

6. Be alert to personal stress and duress. In addition to the organizational stresses mentioned above, more often than not, economic downturns tend to generate significant personal stress and possibly even duress. Even some of the best managed aviation businesses end up reducing their workforce during prolonged economic downturns. And even if a given aviation business successfully avoids workforce reductions, the spouses, partners or other family members of its employees might well be subject to occupational uncertainty and the associated stress at their own workplace. Aviation businesses would well be advised to watch out for early signs of workforce stress and duress and adjust their resource base and human factors programs accordingly.

Conclusion

Building and maintaining an effective safety culture is a significant leadership endeavor in its own right in the best of times. In light of current general macro-economic and aviation industry-specific risks, aviation businesses should prepare for a potential downturn. This article suggests six guiding principles for sustaining an effective safety culture during tough economic times and for navigating cost management challenges. These six guiding principles are intended to help aviation business leaders to cut costs where necessary and appropriate without cutting corners.

Dr. Marc Szepan is a lecturer at the University of Oxford Saïd Business School. Previously, he was a senior executive at Lufthansa. His primary professional experience has been in leading technical and digital aviation businesses based in Europe, Asia and the U.S. He received his doctorate from the University of Oxford.