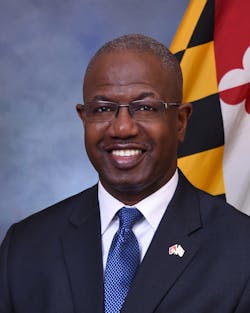

Industry Insider: Ricky Smith Executive Director and CEO of the Maryland Aviation Administration

Ricky D. Smith was appointed as the executive director and CEO of the Maryland Aviation Administration (MAA) by Governor Larry Hogan (R) in July 2015. In his job, he is responsible for the planning, operation and management of Baltimore/Washington International Thurgood Marshall Airport, Martin State Airport, and regional aviation activities in the state.

Smith, a 27-year transportation veteran, returned to MAA after serving as CEO of the Cleveland Airport System for nine years, which includes Cleveland Hopkins International Airport and Burke Lakefront Airport. He was also responsible for overseeing the development and management of the city’s lakefront properties.

During his first tenure at MAA, Smith worked his way up to become COO, where he helped lead BWI Marshall Airport through a $2 billion expansion program, increased air service throughout the world, and created a new food and retail program. He spoke to Airport Business about his career at two airports, overseeing United’s dehubbing in Cleveland, his return to BWI, positioning his facility in the Washington, D.C., metro area and plans for the future.

Airport Business: In your career you’ve been at two airports. It’s rare in this industry. How did you achieve that?

Ricky Smith: I grew up here at BWI Marshall and had no intention of leaving. I left because sometimes you just have to leave your home to become the CEO. That was the only reason why I left for Cleveland. I am an airport professional. I’m not an aviator, so I’m not one who’s willing to go all over the country for an airport opportunity. Cleveland was just one of those opportunities to take on challenges as a CEO and to make a difference in the industry.

If you look at my track record, I’ve been responsible for every major function in an airport. Typically, an airport professional rises to become a CEO either goes through operations, the planning or the engineering sides. And in some cases, they also come from the marketing side. But rarely do you find a CEO that has had responsibility for all major aspects of an airport.

So by the time I went to Cleveland, I had that experience. Sometimes you achieve that by bouncing from one airport to another. I was very fortunate to be able to grow and move around here at BWI Marshall in the 18 years before I left.

AB: You were at Cleveland Hopkins for nine years. What was initially appealing about that job?

RS: Cleveland was an opportunity to take on a challenge that would be impactful. We were about to go through our fourth capital programming cycle at BWI, and we weren’t going to do anything major in the foreseeable future. I like taking on challenges, so when the mayor asked me to consider coming to Cleveland to run the airport system there, I spent some time just trying to understand the challenges of an airport system that was in pretty bad shape.

Its reputation around the country was not the best. The FAA had significant issues with the airport that were holding up funding and Continental Airlines was asking to take over capital projects because the airport system couldn’t deliver on projects. There were a host of other issues and the mayor wanted someone to come in with airport experience to sort through them. So for me, that was a challenge I welcomed. There was an enormous risk with that because Cleveland also had a reputation of running through airport directors. I think at one point, Cleveland had, over an eight-year period, something like 12 airport directors. Colleagues of mine in the industry warned me that I should think twice about taking the job.

It’s important to note my position there was director of port control, which gave me responsibility for two airports, but it also gave me the responsibility of developing the city’s lakefront. So the idea was to try and duplicate what we were able to accomplish in Baltimore with the Inner Harbor. To be able to take that opportunity and marry it with the growth of the airport system was an appealing opportunity as well.

AB: After United Airlines and Continental merged and dehubbed Cleveland Hopkins, how did you work with the airline and the community to manage that process and expectations?

RS: When I arrived, there was already the threat that Continental was going to leave. So the community was very nervous and apprehensive about the future at the time. So my point to the community was that as long as local demand was sustained, even if Continental decided to dehub, someone else would come in and backfill the flights and the community would have the service it deserved. The key was to try and manage the community’s expectations and relieve some of their fears by helping them understand that you may not have United or Continental, but you will have air service.

That was my initial approach, but as I began to develop a working relationship with the leadership at Continental, it became obvious to me that they wanted to grow the hub, but they had some concerns with the management at the airport. So we were able to work through those things and they actually committed to growing the hub. I was there for two years and they announced a plan for a 40 percent expansion at Cleveland Hopkins. That was a big deal for the community. But then fuel prices spiked significantly and that really hit Cleveland hard.

Because the Continental hub there was primarily a regional one, it didn’t have the capacity to absorb the increasing fuel prices, so the hub began to diminish. When United and Continental decided to merge, the philosophy of the leadership was clearly changed. I think [former CEO] Jeff [Smisek] always thought the Cleveland hub was a drag on the system. The hub began to die by a million cuts, starting with the decision to pull out of Paris and London, which were key international cities.

It became obvious to the public that they were drawing down the hub. What I tried to do to stave that off was to engage the business community in a way that allowed them to understand what was going on and allow them to communicate to leadership at United. The airline made it very clear that Cleveland would have to earn its hub. The business community would have to come with a plan to show support for the hub. The mayor and a coalition of business leaders came up with a plan with the airport. It involved things like having the major employers in the Cleveland area start travel policies to fly out of the hub even if they lose money because it was in their best interest to try and protect the hub. So in a number of companies supported the idea of steering employees travel on United, which I thought was pretty innovative.

Meanwhile, we worked on our air services development program and had a lot of discussions with other airlines, including some that were already there. The message we were getting is that as long as the United hub was there, they would not commit to Cleveland. One day United came into the office for one of their usual meetings. The only difference was that one of the senior vice presidents came in as well. It was a very emotional meeting for them and they announced to us that they wanted to draw down the hub. It was not something they wanted to do, but they could not sustain it, according to them.

That dehubbing took away about 30 percent of our traffic, which was a significant hit. But by the end of the following year, we had introduced service from JetBlue Airlines, Frontier Airlines and Southwest Airlines. Delta was growing, and American was growing. By the end of the following year, our passenger levels at Cleveland were higher than they were before the hub. So today Cleveland is doing quite well from a service standpoint and I don’t think people there are worrying about the loss of the hub anymore.

AB: You came back to Baltimore a year ago. Why?

RS: You get to a point that after you spend nine years in any organization, you have made all the contribution you could make. When I left the airport, it had the framework for new master agreements with United and the other carriers that would be executed. The food and retail program was performing very well, we had a strong taxicab program and a host of other amenities were addressed.

When the governor Maryland asked if I would consider coming back to run [MAA], the idea of bringing my family back home and working again with my colleagues here at the airport system and being able to make an impact for my home state was difficult for me to turn down. It was a great opportunity for me.

Nine years later BWI is now going through the challenge of keeping up with its growth. We are experiencing enormous growth here and if it is not handled properly, that growth could be lost. So to be the head of the airport system as we go through that, this is the right place to be.

AB: How has the airport changed in the past nine years?

RS: Nine years ago there was so much uncertainty in the business with fuel prices. Fuel costs were spiking and that made it difficult to plan. The issues around security were raw and putting systems in place to best manage that was a big issue nine years ago.

Today, a lot of those issues have been well thought out. We have a stable economy, fuel prices seem to be stabilizing to some degree and Southwest Airlines has renewed its commitment to this market as its East Coast focus city, including a commitment to international service. I think that’s probably the biggest, the most significant change at BWI over the last nine years. It is causing us to have to rethink our capital program to accommodate their growth.

The other change that we’re going through here is we’re becoming a much more performance-driven organization. We now have a strategic plan. It’s the first time we had a strategic plan in 10 years. And that strategic plan is the product of what our stakeholders say they’d like to see happen at this airport.

AB: You have Washington Dulles and Reagan National airport all in the same region footprint. So how do you work to position BWI as an option in the region?

RS: This is one of the more exciting challenges for me with this airport. As it pertains to the Washington area market, we are in competition with Dulles and Reagan. One of the challenges that BWI has had over the last 20 or 30 years is that the first name in our title is Baltimore, so people in other parts of the world, when they’re planning trips to Washington, they don’t view BWI Marshall as a Washington airport, so we’ve had to spend a lot of resources educating the rest of the world that BWI means Washington. We’ve made some progress over the years, but I think what has transformed us is our ability to attract low-fare international service providers. And so we now have people flying in to BWI to get to Washington, not because they necessarily view it as a Washington area airport, but because it saves them money.

We handle more domestic passengers than the other two airports and our growth rate in terms of international passengers is greater than the other two airports. And the reason why we have that posture is because we are a low-cost airport. Our cost per enplanement is about $9.80 per enplanement. Dulles’ cost per enplanement is about $26 per enplanement and National is about $17 per enplanement.

In Cleveland, I learned the importance of fighting for your market share. There’s this unwritten rule with airport directors that you don’t advertise in another airport’s market and most respect that. In Cleveland, we competed with Akron-Canton Airport, which had a very aggressive marketing campaign. It really worked for them and they were able to do it because Cleveland and Akron-Canton share the same media market.

One of the first things I did was to reposition our marketing function here to a direct report. We now have a division of marketing where service development is centered around this notion that we have to be very aggressive in our marketing through advertising, public relation, outreach to the community, customer service and amenities. We now have an expanded marketing and air service development team that’s all focused on driving our message, understanding what our market share is, understanding what our prospective passenger’s travel habits are and surgically aiming our message at them to convince them that in some cases, BWI Marshall is a better choice.

AB: What are your top goals for the next year?

RS: The most impactful thing that we can accomplish here is to transform the workforce, so we’re still pushing the performance management program through the organization to involve every employee. That is a top priority. But we’re also going through enormous growth. Although Concourse A and B are only 13 years old, they are already becoming too small for Southwest Airlines’ operations. We need more capacity on Concourse E which is our international concourse, and there’s more demand for space on Concourse D.

Our security checkpoints, particularly on Concourse D, are stretched. They were not designed to accommodate the traffic that we have here. And the baggage system does not have the capacity to process bags as quickly as they should. So we have a master plan update on the way to address those issues and other issues that we expect to experience over the next 15 to 20 years. In November, we’re going to open our new D/E connector, a new security checkpoint that will allow passengers to get into both the D and the E concourses without going in and out of security. That will introduce a whole new group of food and retail concepts, six new domestic gates, two more international gates and a new expanded arts program for those passengers that enjoy a little entertainment while they’re here.

AB: What will BWI Marshall look like 10 years from now?

RS: We will continue to expand our security checkpoints and as we have more passengers coming through we will make the modifications to the terminal to accommodate those passengers. But we will try and do it in a way that doesn’t lose the open, convenient feel that people have in the airport.

Ten years from now we expect to have a new on-airport hotel that will be one more customer service amenity that our passengers will enjoy. We also plan to have a new air traffic control tower constructed that will allow the controllers to better manage the growing traffic that’s coming here.

At the same time we’ll have new technology to keep up with customer expectations to get through an airport without interacting with someone. Ten years from now, BWI Marshall will look more convenient, it will continue to have that easy come easy go feel, it will be as safe as it's ever been and it will be a model in terms of maintaining security without compromising the convenience that our passengers expect to have in an airport.

About the Author