Industry-level reporting systems such as the U.S. Aviation Safety Reporting System (ASRS), the EASA Confidential Safety Reporting system, and the U.K. Confidential Human Factors Incident Reporting Programme for aviation (CHIRP) have become proven staples of aviation safety management. Aviation businesses – and companies in other safety-critical industries for that matter – should consider complementing these industry-level programs with their own company-internal voluntary reporting systems (VRS) as integral building blocks of their safety management programs.

There are two basic options for structuring a company-internal VRS: Anonymous or confidential reporting. Each of these approaches has advantages and disadvantages. For example, confidential reporting allows for call-back and enables further investigation and clarification of reported information which is impossible in case of anonymous reporting. However, anonymous reporting can result in collection of data that reporting parties might otherwise be reluctant to report due to concerns regarding the reliability of confidential reporting systems.

In general, aviation businesses are well advised to consider configuring a company-internal VRS so that it allows both anonymous and confidential reporting. This article suggests five key steps for setting up, achieving credibility for, and maximizing the returns from an effective company-internal VRS.

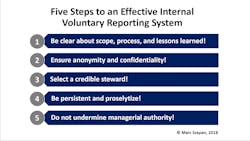

Step 1: Be clear about scope, process, and lessons learned!

Be specific about the intended scope of your VRS. Normally, it is easiest to set up a company-internal VRS that is exclusively focused on aviation safety issues, thereby mirroring the approach of national aviation safety reporting systems such as the ones mentioned above. In this case, other potential noncompliance issues related to – for example – labor, environmental protection, taxation, and anti-trust laws fall outside the scope of a safety-focused VRS and should be reported through other alternative whistle-blowing channels.

Put in place transparent standard operating procedures for handling reported issues. Keep in mind that the value-added of a VRS tends to be highest in case of reporting that includes specific details sufficient for putting in place corrective and preventive measures. Mere “venting” or “complaining” might be cathartic but usually generates only limited organizational mileage. So encourage reporting and as easy as possible reporting that includes sufficient actionable technical and, if applicable, human factors-related details.

A VRS black hole approach is not advisable. Transparent and timely feedback regarding reported issues and related lessons learned tends to encourage future participation in VRS and enhances an organization’s safety culture at large. So commit to realistic and reliable response times for reported issues. Create company-internal transparency with regards to lessons learned developed from information reported via a VRS. Consider disseminating these to your entire workforce via regularly published company-internal versions of safety newsletters or bulletins such as ASRS’s CALLBACK or CHIRP’s Air Transport FEEDBACK.

Step 2: Ensure anonymity and confidentiality!

Ensuring anonymity for anonymous reporting should be a no-brainer. Surprisingly, some aviation businesses manage to get this wrong. For example, one particular company runs an otherwise world-class safety management system that features an internal VRS. However, it only provides one electronic channel – via the company’s intranet – for submitting “anonymous” reports. Submission is contingent upon an employee logging in via her/his company ID badge and individual access code. So much about “anonymity”! Make sure that your VRS allows submission of truly anonymous reporting via securely encrypted online forms from any computer with internet access, email to a dedicated company email address, or even traditional snail-mail to a dedicated company post box address. You could also make use of good old letter boxes in which reports can be dropped off manually and which are placed in areas not subject to CCTV surveillance.

In the case of confidential reporting, the reporting person must have the assurance that reported information will be treated truly confidentially and, as core part of a nonpunitive culture, will not result in adverse consequences for the reporting person. Adverse consequences to be avoided can range from basis disciplinary measures like letters of reprimand to negative implications for the reporting person’s career development and also include legal issues such as loss of employment.

Remember the “single failure trap:” It only takes one single breach of anonymity or confidentiality to undermine efficacy of the entire VRS! So approach protection of anonymity and confidentiality with a zero-error, must-not-fail spirit.

Step 3: Select a credible steward!

The importance of selecting the right leader who is well positioned to exercise credible stewardship of a VRS cannot be overstated, especially in case of a VRS that includes confidential reporting. Credible stewardship is contingent upon a leader’s ability to protect the confidentiality of reporting parties and authority to wield sufficient organizational influence to translate reported information into tangible lessons learned.

Hence the ideal steward for a VRS is a proven and widely respected leader who is trusted by but not substantially dependent on – think of independence as a function of strength of personality, professional maturity, resume equity, professional network, and personal background – the CEO or any other member of the senior management team.

In the end, a reporting person needs to have the confidence that whoever has ownership for a company-internal VRS is both willing and able to maintain confidentiality even in the face of potential pressure to reveal the identity of the reporting person and to say No! to the CEO or any other senior leader. Similarly, credibility of the VRS throughout the organization at large is contingent upon received reporting being utilized in the interest of maximizing safety and not being misused for internal turf-battles or worse. The last person an aviation business should put in charge of a company-internal VRS is a crony or lackey of the CEO or of any other member of the senior management team.

Step 4: Be persistent and proselytize!

Aviation businesses that newly launch a VRS often face two major challenges: First, there can be misunderstandings regarding the intended scope. A favorite example is an aviation service provider that proudly set up what was supposed to be a safety-focused anonymous reporting system. The inaugural submission, however, turned out to be a complaint about the pricing and quantity of meals in the staff dining hall. Second, there can be skepticism regarding the protection of anonymity or confidentiality and the degree to which an aviation business is committed to learning and enacting change based on VRS submissions.

Resolving the former usually entails patience and, at times, a healthy sense of humor. Addressing the latter is likely to require considerable persistence and consistent messaging on the part of the senior management team. So give serious thought to the best ways of championing a company-internal VRS. Make VRS submissions a key part of the standard agenda of senior management team meetings and all-hands-on-deck events to signal importance and commitment. Use every other appropriate opportunity like meetings with smaller employee groups to showcase lessons learned derived from your VRS. And do not forget the aforementioned “single failure trap”!

Step 5: Do not undermine managerial authority!

A company-internal VRS can be a powerful addition to the managerial toolbox for any aviation business. However, overreliance on a VRS can have the pernicious effect of undermining the authority of a company’s management team. A VRS is most effective as a complement to regular lines of reporting but should not be used as a substitute therefor.

Beware of the dangers of inadvertently creating a denunciation culture by allowing a VRS to crowd out regular lines of reporting. A VRS is supposed to be an additional informational resource but not a tool for policing lower level leaders. Assuming the absence of criminal, unethical, or deliberately negligent conduct, leaders whose areas of responsibility are affected by a VRS submission should not be penalized.

Also, make clear that a company-internal VRS is not meant as a substitute for national reporting systems such as ASRS or CHIRP and that employees are at liberty to avail of these national reporting systems.

A company-internal VRS can be an important building block of the safety management system of any aviation or other safety-critical business. In addition, in cultural environments characterized by strong bias against publicly speaking up or questioning authority figures such as a line superior, let alone members of the senior management team, a company-internal VRS can be a natural channel for securing employees’ insights that, due to cultural norms, might otherwise not be accessible. The five steps outlined above can be a good starting point for setting up, achieving credibility for, and maximizing the returns from an effective company-internal VRS.

Dr. Marc Szepan is a Lecturer at the University of Oxford Saïd Business School. Previously, he was a senior executive at Lufthansa. His primary professional experience has been in leading technical and digital aviation businesses in Europe, Asia, and the U.S. He received his doctorate from the University of Oxford.