Jeff Walsh remembers one winter day back when he worked deicing operations for American Airlines at O’Hare International Airport.

“I'm up in the tower and one of the tower coordinators tells me, ‘Jeff, this guy’s been deicing a plane for an hour,’ ” Walsh says. Sure enough, Walsh looks out from his vantage point to one Super 80 sitting at a gate.

“It's the last airplane sitting there, and there’s a river of red glycol going four gates down the terminal,” he adds.

After talking with the deicer, Walsh found out something he’s been trying to address ever since. There’s a lot at stake when deicing aircraft. Most deicing operators want to make sure the plane is perfectly clear of ice as if it were August at ORD rather than February. And with only the best of intentions to get the job right, many operators end up wasting too much fluid.

“We never ever want to jeopardize the safety of the deicing process,” Walsh explains, “but there are operators that just use more fluid than necessary.”

What they need, he says, is a jolt of confidence to know the proper way to perform deicing effectively and efficiently.

Walsh, who was recently made executive vice president, worldwide sales and service for Global Ground Support, Olathe, KS, thinks his company may have developed a way to bolster that confidence through a combination of telemetry, technology and training.

THE QUEST

Walsh has always taken an interest in technology and training.

When he worked for American Airlines for 11 years between 1993 and 2004, Walsh tinkered with a number of patched-together tech odds and ends in a quest to build one information system that could make better sense of his deicing operations.

“The technology just didn’t exist,” he says. “Plus, it was all very expensive and still very limited in the information we could track.”

So after Walsh joined Global in 2004, developing a better information system for the busy deicing manager he used to be was definitely on his check list.

However, the first product Walsh helped create was the company’s Deicing Simulator, a 3D computer-based training simulation system that provides an operator with the ability to practice and take a “performance test” while performing a virtual aircraft deicing event.

Globe’s full-featured deicing simulator allows the user to deice and anti-ice different aircraft under a wide range of weather conditions. Two joysticks control all boom, cab and nozzle movements with the exact speed and commands as the actual Global enclosed cab controls out on the ramp.

Only after developing a number of other products, including a patented deicing blending system, did Walsh turn his attention to what eventually became known as MIDAS - Management, Information, Database and Accounting System.

TELEMETRY

MIDAS essentially allows anyone with approved access to view live data on any of their deicing trucks with any internet-connected device on “fleet dashboard.” The system can be purchased on new vehicles or retrofitted on any manufacturer’s equipment. But that’s just a start.

The program’s most basic function is as a truck telemetry system.

“The system tells users where the trucks are and what the status of each vehicle is,” Walsh explains.

In addition to utilizing the output from the truck's flow meters, MIDAS takes advantage of all of the other system outputs, and uploads that information to the database as well.

The system uploads data from the onboard systems that include the following:

- Chassis engine.

- Auxiliary engine

- Cab and truck heaters.

- Fluid levels from all tanks.

- GPS location.

“As a result of this real-time information, MIDAS also functions as a dispatching system,” Walsh says. “Managers sitting in the tower can dispatch these two trucks to this flight and then these other two trucks to that flight,” Walsh says.

Any maintenance issues can also be red-flagged and provide maintenance crews with information to troubleshoot remotely.

Throughout the day, the fleet dashboard prioritizes the live status information of deicing trucks, and puts critical problems to the top so managers can stay one step ahead of any critical issue throughout the day.

TECHNOLOGY

Once an operator begins a deicing event, managers logged in to the telemetry reporting website can see each truck's fuel, deicing fluid, and anti-icing fluid levels in real-time.

An operator's performance is tracked to include the following metrics:

- Number of gallons of glycol fluid used per aircraft.

- Average number of gallons used per square-foot of wing surface area.

- The amount of time they spent deicing each aircraft.

- The total number of aircraft sprayed per shift.

After a deicing operator has finished deicing an aircraft, all of the data from the completed event is uploaded to the database, and instantly available to fleet managers.

Operators only need to enter the tail number from the aircraft they've deiced in order to transmit the event's details to the database. When the system receives the data, it cross-references the aircraft tail number with the Federal Aviation Administration database and grabs more information regarding the operation that has just occurred.

This information includes:

- The model of aircraft being deiced.

- The aircraft's total wing and tail stabilizer square-footage

- The airport code where the deicing event occurred.

When he was developing MIDAS, a definite no-go for Walsh was any requirement of a dedicated terminal in order to view the data.

Instead, MIDAS is web-based, and anyone with the correct log-in using a Windows-based component, which could be phone, laptop or tablet, can view all the information from pretty much anywhere with an internet connection.

Walsh also didn’t want deicing operators to spend any time inputting data.

“Anytime there’s any interaction with the hardware, it sends that bulk of data,” Walsh adds.

TRAINING

Armed with all this information gathered automatically throughout the day, Walsh says his customers now have an effective database to match an individual deicer’s performance against station averages.

“There's a minimum that you must apply for deicing in order to meet holdover times,” Walsh says, “but I get asked this question all the time: How much fluid will I use to deice a 747? That is a question I refuse to answer because it all depends. It all depends on the type of precipitation. How much snow is already built up on the aircraft? What are the winds like? How many trucks do you have? There are so many variables that will affect the amount of fluid required to safely deice an aircraft.”

With a station average, each operator can be ranked where they stand on the quantity of fluid used per square area by type of aircraft as well as other performance metrics, such time of operation and how many aircraft were deiced per shift.

“All these different measures and variables go into an operator’s ranking,” Walsh adds. “That way managers can identify which deicing operators are most in need of improvement. One thing that I discovered while working at American that seems to bare out with our customers is that the bottom 15 percent of employees sprays 40 percent of the fluid.”

Walsh, however, says this information won’t serve any purpose if it’s used as a disciplinary tool.

“It’s meant to be an aide in improving the operation,” he says. “Our customers never want to say, you need to spray less fluid on an airplane. What the operator needs to know is how to feel confident to spray enough fluid to clean off the aircraft.”

Which, as you may have guessed, is exactly where Global’s simulator can be put to perhaps its best use.

“The simulator goes a long way toward helping operators build that muscle memory and understand how to operate the vehicle,” Walsh says. “All of those things go hand in hand with having a safer operation and using less glycol.”

Walsh finds that most operator errors are the result of distance.

“First off, if operators don’t feel confident using joy sticks and the boom controls, they might not want to get within the 2 to 5 meters that they need to be from the surface of the aircraft. They’ll play it safe and stay back 7 meters.”

Operators may not hit anything that far away, but Walsh says they’ll always end up using too much fluid.

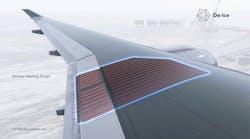

“In actuality, deicing is a thermal process,” Walsh says. “We're using the heat of the fluid to deice that snow and break that bond from that ice and the surface of the aircraft. The fluid keeps melted snow and ice from refreezing again. The farther an operator is from the aircraft surface, the glycol will lose a specific amount of temperature for every foot.

Global’s simulator has also gone through improvements since its introduction when it featured two types of aircraft and one type of deicing truck. The current version now features 16 planes and three models of truck with additional improvements on wind speed, wind direction, precipitation type.