DFW’s Perimeter Taxiway

According to the National Transportation Safety Board, there were 327 runway incursions in fiscal year 2005, and 330 in 2006 — numbers that everyone in the aviation community would like to see drop. At Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport, officials are being proactive in seeking new methods and new technologies to prevent runway incursions. In October, the airport began construction on the first quadrant of its perimeter taxiway system, which will allow aircraft to taxi around the end of its seven active runways instead of waiting to cross them. The system is expected to significantly decrease runway crossings, thereby increasing safety and efficiency, thereby reducing the probability of an incursion.

According to Jim Crites, executive VP of operations at Dallas/Fort Worth International, the airport sees, on average, 2,000 aircraft operations per day on its seven active runways. The configuration of the DFW airfield requires some 1,800 daily runway crossings.

At any airport with parallel runways, explains Crites, there are going to be runway crossings by arriving aircraft that will have to be carefully orchestrated by air traffic control and the pilots. “It’s a lot of effort,” he says. “It’s not a big stress thing when you’re working with maybe three airplanes. But when your arrival rates and departure rates per hour on those two runways start to build, you can imagine you’re starting to talk to a lot of aircraft. And what ends up happening is, in order to get all these arriving aircraft to cross, the air traffic controller has to start increasing the in-trail separations for departing and arriving aircraft.”

A perimeter taxiway allows arriving aircraft, instead of crossing an active runway, to taxi around the end of the runway. This keeps the air traffic controllers and pilots from getting “bogged down” in communications to safely manage runway crossings, Crites says.

A Key to Study:

Simulation

DFW partnered with NASA and the FAA to simulate the perimeter taxiway system. Air traffic controllers and pilots who work at DFW completed a virtual test of the system at the NASA Ames Research Center at Moffet Field, CA.

Crites says the study cost some $400,000 but was priceless in giving the airport, air traffic controllers, and pilots the real data they needed to determine if the perimeter taxiway idea was sustainable. “That might seem like a lot,” Crites explains, “but since we spent probably $750,000 in computer simulations and never got the answers we got out of the human-in-the-loop simulation [at NASA Ames] — it’s money well spent.”

Thanks to the simulation, Crites says he and his team “have a high degree of confidence that when the taxiways are operating in 2008 that the pilots and controllers will be extremely satisfied.”

It took roughly six weeks to set up the simulation at NASA Ames so when controllers looked out of the “tower” what they saw was a replication of the actual DFW airfield, and all the aircraft operating there. Similarly, pilots in the simulation saw the DFW airfield as well as the other aircraft. “It’s like you’re really there,” says Crites. “It’s not like a computer model where maybe you’re making an estimate of how fast aircraft taxi. They’re actually seeing how fast they are taxiing, where aircraft really are.”

When DFW simulated its operations environment at the NASA Ames facility, the airport’s operations schedule, which was already “quite high,” according to Crites, was increased by some 30-35 percent. “What we found in the simulation,” he says, “is communications were reduced by 27 percent between the controllers and pilots — which was super. It freed up the airwaves, simplified the pilots’ and controllers’ lives.”

During the simulation — even after boosting operations beyond the normal DFW flow — the air traffic controllers actually ran out of aircraft, Crites says. “That means there’s a 35 percent increase in effective capacity of the airport; that’s huge.”

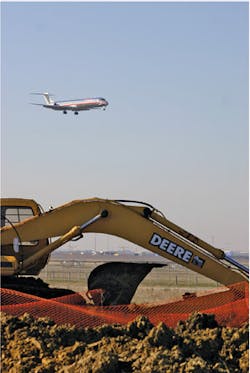

Construction ‘Nearly Unnoticeable’

Crites comments that the construction of the perimeter taxiway system, which began in October 2006, is “nearly unnoticeable on the active airport operations area.”

The perimeter taxiway is divided into four quadrants and will come online in phases, with the first phase — around the southeastern quadrant of the 18,000-acre property — expected to be complete by fall of 2008. “We want to put in the first quadrant to verify that all of our best thinking on the part of the pilots, controllers, FAA, airport, and the airlines is going to be realized,” says Crites.

Once the first quadrant is operational, the airport expects to get feedback from operators on the field before proceeding with the final three phases.

The cost of the first quadrant is estimated at $66 million, which includes the cost of relocating a roadway, Crites says. The taxiway itself is roughly $42 million for each quadrant. “So for about $168 million, I’ve just increased the safety of this airport, eliminated runway crossings, and boosted the efficiency of the airport by 35-plus percent — you can’t buy that with a new runway. You can’t buy that with probably two new runways.”

The system will extend an additional 2,650 feet from the end of the runway and Crites says that even though it means an additional two minutes, on average, in taxiing time, it is a very deliberate number. “The reason why it’s 2,650 is we’re looking at not only allowing aircraft to taxi under a departing aircraft, but we want to be able to taxi underneath arriving aircraft to the inboard runway,” Crites says.

“By allowing aircraft to taxi on a perimeter taxiway, underneath an arrival stream, this allows them to have unrestricted feed to both runways for departure scenarios, and to do so safely.

“Once again I’m eliminating more runway crossings, reducing communications, eliminating the runway incursion potential, and maximizing the efficiency of the airport to its original design levels because we don’t have any of these interactions going on.”

The distance the perimeter taxiways are from the runways is such that they will be clear of the TERPS (Terminal Instrument Procedures) surfaces — imaginery surfaces that should not be penetrated to provide the maximum enevelope of safety for operating aircraft, explains Crites.

And even though taxiing time will be increased by some two minutes, aircraft should experience an overall improvement in time operating at the airport.

Comments Crites, “Where you make up for this is you’re not waiting to cross a runway and you’re moving more aircraft during peak periods — your out-to-off times decrease 4.28 minutes. So, at the end of the day, I’m reducing your overall time operating by 2.28 minutes.”

Safety, of course, was the original goal intended with the perimeter taxiway, but the bonus benefit is it “restored, at high traffic levels, the optimal capacity of the runways because you deconflicted the operations,” says Crites. “They don’t overlap; they’re independent of one another instead of dependent on one another... Another way to frame that is, no matter what the traffic level intensities, the airport can always operate at the original traffic capacity design levels that the FAA and the airport had in mind for those runways.”

Other good news for the project, says Crites, is that it does not adversely impact the communities surrounding the airport. Because aircraft will spend less time operating at DFW, emissions will be lower and, at the same time, airlines will save money on fuel. “It’s a win-win-win across the board from safety to efficiency, to community relations, to environmental,” he says.