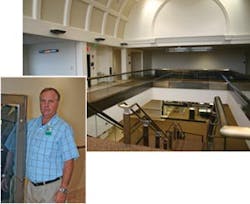

PLATTSBURGH, NY—In April 2007, Plattsburgh International Airport (PBG) dedicated a brand-new, $10 million 35,300-square-foot terminal building. On June 18, it opened its doors to commercial passenger service in and out of this former Air Force Base located just one hour south of Montreal (see story). Owned and operated by Clinton County, airport manager Roger B. Sorrell, C.M. and other supporters see a bright future for this facility, which is already operating in the black, thanks in large part to the non-passenger activity here.

The 1,699-acre Plattsburgh Air Force Base was the longest active military installation in the United States, and had been connected with the military in one way or another for more than 40 years.

According to airport officials, Plattsburgh AFB was created in the 1950s as a base for the Strategic Air Command and was continually modernized by the U.S. government until its unexpected closure in 1995.

The Clinton County government took over operation of the facility, and the footprint at PBG was increased to 5,000 acres, making it a “regional, multi-purpose aviation and aerospace complex,” according to officials. The Clinton County Airport, some three miles northwest of PBG, was also operated by Clinton County, but was closed to focus development on Plattsburgh.

According to airport manager Sorrell, the capital for the investment to transform the airport for civilian use came from three sources: FAA paid for 95 percent; 2.5 percent came from New York State; and another 2.5 percent contributed by Clinton County.

Sorrell’s predecessor, former airport manager Ralph Hensel, along with the county legislature worked on funding for the new terminal, according to Adore Kurtz, president of The Development Corporation, a locally based company hired by Clinton County to assist with the transition.

“Getting the facility ready to be an airport cost about $20 million, the bulk of which came from FAA,” she says. “Thirteen million dollars of that supported the terminal, the jetway, and other things.”

Sorrell says the terminal is designed and located to allow plenty of capability for natural expansion.

[As we go to press, changes were announced at Plattsburgh International, with manager Sorrell resigning after some nine months on the job, citing personal reasons. Rodney Brown, Clinton County planner and deputy administrator, has been named the interim director.

Thinking through the terminal

Hensel and the legislature put a committee together to look at how to make a terminal that was appropriate for current operations, but expandable.

“We didn’t want to build JFK; on the other hand, we really knew there was potential for growth in passenger service,” explains Kurtz at The Development Corporation.

“All of us have been to the airports where you have to take a shuttle bus to some other terminal. Well, they tried to circumvent that and also wanted to work on the legacy of the architecture that the Air Force, Army, and Navy left for us. The design looks more like a military base.”

Sorrell says that they are working on a number of other renovations around the airfield. He is currently improving nose docks, which were initially designed for military planes, and will be looking to lease out the space once they’re completed.

“A lot of these buildings need to be renovated or demolished,” he says. “They’re 40 years old, and if you don’t use a lot of these buildings, they’ll just deteriorate before your eyes.”

The airport has had to deal with some pollution on the site, but Kurtz says that at the time that the Air Force base was closed in 1995, it was considered one of the cleanest facilities. “That’s not to say that there haven’t been millions of dollars spent on the airport facility and the rest of the base,” she says. “We feel that we know where the problems are.”

Tenants Key to Development

Plattsburgh’s anchor tenant thus far has been the Department of Homeland Security (DHS). Airport manager Sorrell says DHS uses the airport as the base for its northeast operations, spanning from the New Jersey border to Maine. “One of the advantages that (DHS) liked about Plattsburgh is that we are really close to Lake Champlain and they can monitor the waterway up into Montreal,” Sorrell says.

Along with DHS, Plattsburgh International has some 80 tenants, including:

- Pratt & Whitney, which has an engine-testing site inside the fence;

- the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, which has a mobile laboratory to test items coming across the border;

- the Plattsburgh Aeronautical Institution;

- Clinton Community College;

- Exelon Powerlabs; and

- Wyeth Pharmaceuticals.

In total, the airport now employs more people than when the Air Force was here.

“There is plenty of industrial space,” says Sorrell about the possibilities for current and future tenants to develop. “And there’s not an airplane in the world that we can’t handle.”

One prospective industrial client Kurtz says that PBG is currently working with is the start-up company Laurentian Aerospace. The two have been working together for nearly a year and the plan calls for Laurentian to service ‘C’ and ‘D’ checks for wide-body aircraft. Laurentian is currently in the final stages of getting financing and expects to break ground soon, she says.

Laurentian Aerospace Corpora-tion’s building will be a state-of-the-art maintenance/repair/overhaul (MRO) facility, offering heavy maintenance for wide-body aircraft. Its two-bay hangar — approximately 224,000 square feet and capable of servicing everything but the A-380 — is planned to open in the fall of 2008 and will stand 110 feet tall.

Kurtz is optimistic that by handling wide-body aircraft for Laurentian, other airlines may be attracted by the airport’s familiarity with large aircraft operations on the ramp.

“We know that when Laurentian is here, we’re going to get wide-bodies and there aren’t many small towns and cities that have an airport that needs the GSE (ground support equipment) support for big aircraft,” Kurtz says.

“There is a financial commitment to make sure that the ground service equipment can support what we know is going to happen. We are confident that we will have [wide-body aircraft] flying in here for maintenance and we have to prepare for that.”

Because of the success PBG is having with its industrial clients, the airport is already operating in the black. “[That] is empowering and helps support the additional manpower and provide infrastructure,” Kurtz says. “It enables us to have low landing fees and a reasonable fuel flowage fee…

“We have an industrial airport right now that gives us the ability to be patient about development. If the community saw the airport as a financial drain, and they didn’t know at what point that might turn around, that would be a problem.”

Air service; getting an FBO

Despite the positive growth at the airport, it has had some issues attracing a fixed base operation (FBO), and passenger services haven’t taken off as fast as planned.

In August, SheltAir Aviation Services, based at Fort Lauderdale Executive Airport, announced it had entered an agreement with Clinton County to provide FBO services.

In a release, Ed Zwirn, COO of SheltAir, comments that the airport’s location — one hour south of Montreal and near a major Interstate — and the support the airport has received on both the local and federal level make Plattsburgh a prime location for SheltAir.

The airport had reportedly been in discussions with both Aero Toy Store and Million Air, but an agreement was not reached with either.

Kurtz and Sorrell anticipate that the initial passenger growth will come from low-cost airlines that fly direct to vacation destinations, which, according to Kurtz, is something that there is an enormous demand for in Canada. She predicts that within a year, there will be at least two new destinations served.

PBG is also working with Canadian tour businesses to offer charter flights that they can accommodate immediately, she says. “A low cost carrier that goes to multiple locations would be very attractive,” Kurtz says. “JetBlue and Southwest are both attractive to us.”

“We are going to start out small with the commuter jets, and then start growing with the vacation packages and hopefully keep expanding our industrial base,” Sorrell says.

Lessons Learned

During the transition, says Kurtz, expectatations by some for immediate air service may have been unrealistic. “We really needed to build the facility, but we should have tempered the expectations about how quickly we’d have more than our commuter airline here,” she says.

CommutAir, working with a Continental Airlines connection, operates the same amount of service as it did at the Clinton County Airport, using B1900s. Sorrell says they offer some four flights per day; passenger services have been terminated on Wednesdays to try and fill more seats.

Says Sorrell, “The engineers and airport professional designers should have had a better relationship with outside agencies such as DHS and TSA (Transportation Security Administration). We’re finding out now that there are requirements that weren’t built into the building, and at the time when they initially designed the terminal they weren’t a requirement.

“It’s to the point where we are brand new, we just opened; and we’re already making modifications to support TSA requirements,” Sorrell says.

“We’re trying to [incorporate] them in the design of the building. We need security, but I don’t want wires hanging out outside of these brand new walls.” Sorrell notes that the airport will be adding 300-plus square feet of space for a TSA training room that was not initially designed.