Past Contact! Mechanics in Aviation History

In the summer of 1910 Minneapolis hosted one of America’s earliest exhibition air meets. William Bushnell Stout, age 30, was there when aviator Eugene Ely’s Curtiss biplane made a low flight that crashed into a fence.

“I was hired as a mechanic by Ely, to help him build his machine into shape for the next day’s flight,” wrote Stout in his 1951 autobiography, So Away I Went! Stout’s masterful hands-on career with aircraft lasted decades. His projects connected him with the most influential men in transportation development — among them Henry Ford, Igor Sikorsky, and Octave Chanute.

“Bill” Stout was born in Illinois and was an unusual person from early childhood. Although his poor eyesight was nearly debilitating, he possessed curiosity, ambition, and passion for all things mechanical. He loved toys, and as a teen invented gadgets made from paper clips, kitchen spoons, newspapers, sewing thread, and soap, which he sold in magazines. One of his earliest designs was a paper airplane powered by a rubber band. In later years he founded a national model airplane club and always believed that if a person created something that flew with their own hands, they would become better design engineers, pilots, and mechanics.

Stout graduated from Mechanical Arts High School in Minnesota then traveled to Europe with the bare necessities to expand his world view. He entered college but dropped out, embarking on his own learning path.

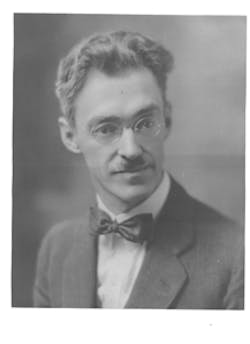

Few men were as naturally gifted with diverse talents as bespectacled Stout. He was an artist, able to sketch images of outdoor scenes for pleasure and technical drawings for engineering designs. He was a poet, publishing two booklets of his own words. He was a musician, enjoying an impromptu jam. He was a prolific journalist, hired by some of the most popular magazines and newspapers of his time. He was a frail and thin man but he worked long hours, and pushed himself physically to meet a promised deadline or test one of his machines.

In 1906 Stout married Alma Raymond whom he later described as his “inspiration for everything.” They moved into a small shack in Minnesota where Stout built their first furniture. They raised a family and spent a lifetime together.

Stout’s hundreds of patented inventions range from simple children’s toys to the first major changes in motorcycles, cars, airplanes, trains, and even portable housing. Were he alive today, Stout might be designing spacecraft or developing “green” transportation. Modern technology is still catching up with the man who never stopped tinkering.

By 1907 Stout was chief engineer for a truck company and in 1912 the Chicago Tribune hired him to edit their automotive section. With friends he founded Aerial Age, one of the first magazines solely dedicated to aviation. Wild about motorcycles, Stout began designing his own in 1910 (the Bicar, the Cyclecar, the Victor) and progressed to automobiles (the Scripps-Booth). By 1916 he headed sales at Packard and became the chief engineer of its new aviation division. During the 1920s Stout was an outspoken advocate of building all-metal airplanes, facing ridicule and resistance from those who built aircraft made of wood. He also held strong convictions about the future of power plants. He once pointed out to an unimpressed Army officer that “It is just as silly to water-cool an airplane engine as it would be to air-cool a motorboat with all that water.”

Between 1918 and 1922, Stout formed Stout Engineeringanddeveloped the airworthy, all-wing (36-foot) Batwing and the Torpedo Plane constructed of Duraluminum, for the Navy.

Safety, reliability, and luxury

Between 1922 and 1923 Stout built America’s first all-metal commercial airplanes which evolved into the eight-passenger Stout Air Pullman(the 2-AT), powered by a Liberty engine. Radically different than anything previously flown, the exterior was corrugated metal and the cockpit (which was protected by a celluloid wind screen) was designed for a pilot and co-pilot. Inside, wallpaper, padded seats, and a bathroom created luxurious comfort. When the 2-AT was used to haul cargo Stout called it the Air Truck.

Henry Ford bought several 2-ATs and formed Ford Air Transportation Service. Next to his Detroit plant in 1925, Ford built an airport, factory, and hangar for ongoing aircraft development by the Stout Metal Airplane Company, which he soon purchased to become the Stout Metal Airplane Division of Ford Motor Company. Stout Air Services flew regular routes to Minnesota, Illinois, and Ohio, and in the early 1930s sold out to United Airlines.

Stout’s next aircraft project failed, prompting Ford engineers to assume the redesign of a three-engine passenger plane. Nevertheless, Stout’s all-metal aircraft led to the successful Ford Tri-Motor. Author Henry Holden has often written about Ford Tri-Motors. “The impact of [the] Tri-Motor,” says Holden, “is one of the milestones in the history of American commercial aviation.”

Between 1927 and 1929, Stout invested in Scenic Airways Inc., a company with the far-reaching goal to fly passengers on an aerial tour over every national park in the United States, setting up its first airport 15 miles south of the Grand Canyon. In 1930 Scenic’s airport was taken over by Grand Canyon Air Lines, which flew several types of aircraft including the Ford Tri-Motor.

Between 1932 and 1934,Stout Engineering built the round-bodied Stout Scarab car with a rear engine and a luxurious interior. It was too different for the public to buy. Among Stout’s other unusual designs were the Aerocar, which had detachable wings and could be parked in an automobile garage when not flying. He designed a rear-engine bus, and built the Railplane, a gasoline-driven Pullman train car. He invented a conveyor for a brick factory, and movable movie theater seats, as well as an air-cooled bed. “Stout,” says Holden, “was regarded by many as eccentric but by all as brilliant.”

Our first military A&Ps and the folding roadhouse

As the United States entered WWI, Stout volunteered assistance for the hastily formed maintenance division of the Signal Corps (later the Air Service). “A group of [45] motorcar mechanics were leaving the next night for France to do airplane repair work,” recalls Stout, “but none of them knew anything about an airplane.” In less than 24 hours Stout produced an illustrated text as a manual and handed a copy to each man which was later published as a textbook in the “aviation war effort.”

During WWII Stout was unimpressed with the quality of travel trailers and built one of his own for his family. It had folding walls which made a 16-square-foot room that could be put up quickly by two people. He began manufacturing the Stout House and soon sold them to the military. Stout wrote that during the war, “These houses went all over the world. They could be knocked down and put inside a B-24. Many were equipped as engine repair stations with bunks in the wall on one side and workbenches on the other. They were complete with a heating system which would use anything, but worked particularly well with 100-octane aviation gasoline.”

In 1943, a columnist for Mechanix Illustrated described Stout as “characteristically Midwestern and homespun.” He experienced successes and failures, but was known as a fair and ethical businessman. During financial difficulties Stout recognized that the hardships of one are the hardships of all. His words are timeless. “We have proved ... that you cannot get wealthy by taking it away from someone else. It melts away like snow in your hands.”

Stout retired to the warm climate of Arizona and died in 1956 at the age of 76. Late in life the man that had invented and loved everything on wheels wrote these final words:

“They say you have made a good landing if you can walk away afterward. Long habit has made me prefer to ride, but if necessary, I’m prepared to walk.”

Giacinta Bradley Koontz is an aviation historian and author. She was the founder and director of the Portal of the Folded Wings Shrine to Aviation and Museum from 1995-2001 (the site of Charles Taylor’s grave in North Hollywood, CA). Giacinta holds a bachelor of arts degree in anthropology with a minor in U.S. history and has given presentations on pioneer aviation since 1995. Most recently she has been awarded a partial grant from the Wolf Aviation Fund to write her second book, highlighting the life of Amelia Earhart’s mechanic, Ernest Eugene Tissot Sr.