California's Off-road Diesel Regulation Moves Forward

California’s in-use off-road diesel vehicle regulation (ORD) is moving forward, and fleet operators in the state need to take note. Written idling policies need to be in place by March 1 for medium and large fleets, and all fleets need to begin annual reporting this year. After March 1, Tier 0 vehicles may no longer be added to off-road fleets. Large fleets need to have compliance plans in place as soon as possible, as the deadline for performance requirements for large fleets is in 2010.

Describing how ORD will impact fleet managers, Tim Wix, of Averest Inc. and former GSE manager, doesn’t sugarcoat his words: “ORD will make the life of fleet managers very difficult. They are going to have to develop a strategy to meet the regulation and then sell it to upper management. This will be a difficult task in the current economic environment.

“They need to understand that there will be heavy fines for noncompliance and a strategy is required — now,” he says.

Effective under California law since June 15, 2008, ORD is aimed at reducing particulate matter (PM) and nitrogen oxide (NOx) emissions from the state’s estimated 180,000 off-road vehicles used in construction, mining, airport ground support and other industries. The term “off-road vehicles” does not include stationary or portable equipment. It only includes equipment with a diesel-fueled or alternative diesel-fueled off-road, self-propelled, compression ignition engine that is 25 horsepower or greater. The rule applies to any person, business or government agency that owns or operates diesel-powered equipment in California. Yet, knowing California often leads clean air regulation and other states follow, fleet managers outside California will want to pay close attention to ORD.

GSE that’s subject to regulation fits primarily in four categories: aircraft pushback tractors (and towbar lifts), cargo loaders, cargo tractors, and baggage tugs or tractors.

“That’s probably about 90 percent of the airport GSE that’s covered under the regulation,” says ARB air pollution specialist Beth White.

She points out other GSE may fall under other off-road regulations, such as Off-Road Large Spark Ignition (LSI) and portable equipment rules established by individual air districts. Fleet managers can look at off-road mobile source regulations by going to www.arb.ca.gov/msprog/offroad/offroad.htm. GSE fleets may also have equipment that falls under the On-Road Regulation that was approved by the ARB in December 2008.

Sometimes the definition of a fleet can be confusing. ARB defines a fleet in this case as off-road diesel vehicles in California that are under common ownership. ARB is working on a guidance document to help fleet owners understand that while subsidiaries may have different tax IDs, if they are still under common ownership, the parent company is considered the fleet owner, not the subsidiary. It is the fleet owners who will be held responsible for not complying with ORD.

Although the fleet managers often develop compliance plans and ensure the idling and reporting regulations are met, everyone from the fleet owner to the vehicle operators should understand what they need to do to comply with ORD.

IDLING LIMITATIONS

Five-minute idling limitations became effective and enforceable the day ORD became effective. Some exceptions apply, such as idling to accomplish work for which the vehicle was designed and idling to bring a machine system to operating temperature (See www.arb.ca.gov/msprog/ordiesel/guidance/idling.pdf).

“Make sure the information filters down to the vehicle operators, since the fleet owner is the one who runs the risk of getting fined for noncompliance,” White says.

ARB can assess the owner, renter or lessee daily penalties for each idling vehicle found to be in violation. Each first-time violation of the idling requirements will be assessed a minimum civil penalty of $300. Subsequent penalties can be $1,000 to $10,000.

As of March 1, medium and large fleets must have a written idling policy. (A fleet owner may apply for a waiver to allow additional idling.) ARB doesn’t mandate what needs to be included in an idling policy, but a guidance document is available at www.arb.ca.gov/msprog/ordiesel/guidance/writtenidlingguide.pdf.

“Besides making sure that the operators understand the idling requirements, owners will want to protect themselves in case operators don’t comply intentionally,” White says. “There should be a corrective action procedure in a written idling policy that says, ‘If you’re caught by the company not complying, here’s the consequence.’ ”

INITIAL AND ANNUAL REPORTING

The next deadline approaching is April 1. By that date, large fleets (with a combined horsepower of more than 5,000) must have completed initial reporting. ORD has different reporting deadlines for different fleet sizes. Medium fleets (2,501 to 5,000 hp) must complete reporting by June 1, and small fleets (2,500 or less) must complete reporting by Aug. 1. There are exemptions for inclusion in total fleet horsepower, such as low-use vehicles (operated less than 100 hours per year).

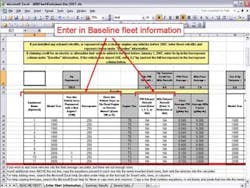

ARB’s Diesel Off-Road On-Line Reporting System (DOORS) (https://secure.arb.ca.gov/ssldoors/doors_reporting/reporting.php) is the primary reporting tool for initial and annual reporting.

The information that initially needs to be reported is substantial. Making sure that information is complete will ensure that fleets owners receive credit for every effort that they make to meet or exceed the performance requirements. Fleet owner, vehicle and engine information need to be entered. If there’s a retrofit, or if a diesel vehicle was replaced by a non-diesel vehicle, or if there’s a stationary or portable system like a conveyor belt that replaced one or more diesel vehicles, that information needs to be included. Any early credit actions (e.g., surplus repower to a higher tiered engine, early retrofits, or a vehicle retired early) also need to be reported.

After the fleet inventory is provided to ARB, each vehicle will receive an ARB-assigned engine identification number (EIN) and the numbers must be on the vehicles 30 days from when they are received.

“If any owners have not yet started to gather data from their engine tags for the reporting requirement,” SkyWest Airlines supervisor of environmental compliance Toby Steele emphasizes, “they should get started now.”

The process can be difficult depending on the age and condition of the engine.

“Some brands will have all the needed information on the engine tag. Others won’t, so you will have to request help from the engine manufacturer to complete your database,” he says.

PERFORMANCE REQUIREMENTS TO REDUCE EMISSION

Following the idling and initial reporting deadlines, feet operators must meet the performance requirements to reduce emissions.

Beginning in 2010, large fleets must meet the fleet average emission rate target for PM — or apply the highest level verified diesel emission control system to 20 percent of its total horsepower. In addition, large fleets must meet the fleet average emission target for NOx or turn over a percentage of its horsepower: 8 percent until 2015, and then 10 percent thereafter.

Medium fleet requirements start in 2013, but are otherwise the same as large fleet requirements. Small fleet requirements start in 2015, however, operators only have to meet the PM requirements.

In all fleet-size categories there are exemptions. For example, vehicles less than 10 years old are exempt from the turnover requirements, and engines in vehicles less than five years old are exempt from the exhaust retrofit requirements.

Fleet average emission targets can be met with different options:

- installing exhaust retrofits that capture pollutants before they are emitted to the air,

- repowering vehicles with newer, cleaner engines,

- rebuilding engines to a more stringent emissions configuration or

- retiring older vehicles and accelerating turnover of fleets to newer, cleaner engines.

Based on input she’s received so far, White says GSE fleet managers predominantly will turn to electric equipment to meet ORD requirements.

It makes sense for fleet managers to turn to electric, according to Rob Lamb, vice president of sales and marketing for Charlatte of America, which manufactures electric vehicles for the ramp. “As regulations become more stringent only electric and other green alternative energy sources protect fleet managers from replacing their vehicles every few years,” he says. “In many scenarios, electric is not only more-user friendly to the operator, it’s less costly to maintain.”

Wix agrees, “The best long-term strategy, in my point of view, is to face the situation one time and convert to electric-powered GSE where possible.”

The benefits to this approach are having a one-time cost and avoiding the labor-intensive bookkeeping associated with the regulation, he says.

Understanding the value and sometimes challenges posed by electric equipment, TUG Technologies Corp. offers a broad product line with both electric and internal combustion alternatives.

The company’s electric options include its 4th-generation electric tractor rolled out last year as well as an electric belt loader. Diesel options from TUG include a Kubota Tier III/Tier IV interim engine and Deutz Tier III engines for large push backs, and soon TUG will be offering a Deutz Tier III engine in its belt loaders and baggage tractors. Gas and LP engines are also available from TUG.

TUG vice president of sales and marketing Brad Compton agrees that electric equipment has tremendous value and often will be the best option. But he points out the infrastructure of GSE operations needs to be considered as well as the specific overall needs of an operation.

SkyWest has fewer than 50 diesel units that will fall under ORD; most are baggage tugs that have engines between 60 and 100 hp.

Steele has found that exhaust retrofit kits for those size engines are nearly the cost of a new engine. That said, he’s looking at replacing engines with new, higher tier engines and replacing diesel equipment with electric. No firm decisions have been made yet.

“I think we’ll probably end up with a mix of new engines and electric replacement,” he says.

SkyWest has been placing as much electric equipment as possible in California for years, and that has helped the airline’s fleet average, Steele says.

Before choosing a final compliance plan, White advises fleet managers to try different compliance paths using the Fleet Average Calculator (www.arb.ca.gov/msprog/ordiesel/documents/documents.htm#fleet). Unlike DOORS, where a lot of information needs to be reported, the Fleet Average Calculator just needs horsepower and model year to calculate fleet average.

COST

The costs associated with compliance will depend on the path chosen to comply with the regulation.

“I believe that if your strategy is to stay with a diesel engine and replace or modify engines to meet the regulation, it will cost you more in the end,” Wix says. “My guess, in the end, is it will cost the industry well over $100 million to comply with this regulation in California. That includes equipment purchases/modifications and additional administrative support.”

In writing the regulation, White says, ARB realized compliance was going to be financially challenging for many fleet owners whose vehicles were going to be regulated.

“Many fleets may have to change how they allocate their capital resources,” she says. “They may need to borrow money to purchase retrofits and repowers or upgrade their vehicles. And we expect 20 to 40 percent of the fleets will need to pass on some of their compliance costs to their customers to remain profitable.”

Understanding that loans aren’t easy to get these days, ARB is piloting a new loan guarantee program in the San Joaquin Valley. If it is successful there, it may be implemented statewide.

Incentive funding — about $140 million annually — is available for medium and small fleets through the Carl Moyer Program, which pays for emission reductions that go beyond the regulatory requirements (e.g., doing more than the regulation requires or complying with requirements at least three years early). Because initial compliance dates are not until 2013 for medium fleets and 2015 for small fleets, they would be able to access funds before the compliance date. Also, because small fleets are exempt from the NOx portion of the regulation, they will always be eligible for projects that achieve NOx reductions. For GSE fleet managers going electric, White points out the Carl Moyer Program includes incentives for the purchase of electric equipment under the eligible projects category.

Regarding the Carl Moyer Program, White says that unfortunately not every applicant will receive funding because there are always more requests than there is available funding. Those who do not receive incentive funding still have the regulatory provisions for economic downturns (such as early credits and utilizing compliance plans that spread out their costs).

SPREADING THE WORD ABOUT ORD

To help fleet managers avoid headaches, ARB held free training seminars in 2008 and currently six are scheduled in February and March. ARB staff is also available to give presentations to fleet owners, equipment dealers or manufacturers. Many resources from ARB are available online.

White also invites fleet managers and owners with questions to contact her directly.

“All change is hard,” she says. “We’re here to help people in any way we can.”

While California is the only state given the right under the Clean Air Act to enact environmental regulations stricter than federal standards, Wix predicts that with the new administration in Washington, ORD is just the beginning of what is to come.

“It will be interesting to see what the new Secretary of Energy as well as the new EPA director have in store not only for California, but the rest of the nation,” Lamb adds.