Part 135s Talk Safety; Security

CHANTILLY, VA — The Air Charter Safety Foundation (ACSF), founded in part by the National Air Transportation Association (NATA) in 2007, recently hosted the 2010 Air Charter Safety Symposium. Hot topics included a ‘steadily’ improving industry safety record, general aviation facility security, and safety management systems (SMS) — with particular focus on the latter regarding concern for operating in foreign states without an internationally recognized/accepted safety management system.

Remarks ACSF chairman Charlie Priester, “In the last few years, we have come to understand as an industry, that an FAA standard for safety is a minimum standard. We owe it to the guests we fly to take that safety level to a much higher standard. We are seeing attitudes change; we are all taking this to a higher level.”

Jim Coyne, president of both ACSF and NATA, followed Priester by highlighting a recent study conducted by the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) regarding air charter safety.

“What this foundation does is critically important,” says Coyne. “It shows the public, and it shows people here in Washington, that we are serious about safety.”

Jim Ballough’s role at the conference was to address the NTSB study by presenting on the implications, opportunities, and challenges that may result from it.

Ballough, senior advisor and special assistant to FAA’s associate administrator for aviation safety Peggy Gilligan, began by pointing out the variety of operations that make up Part 135 activity. “There are those that would contend it’s one single coherent set of flight activities,” says Ballough. “However, much like general aviation, the term captures the collection of very different types of operations.” Some examples of this include air tours, cargo, the business jet market, traditional passenger service, heavy lift, survey, and air ambulance.

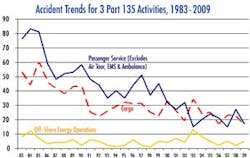

“All industry accidents have gone down over the years, including fatal accidents,” explains Ballough. “In terms of on-demand Part 135 activity per 100,000 hours, again there is the same scenario … trends are improving steadily.

“However, the figures are still high compared to much of the GA environment — but the 135 numbers also reflect the mixed activity within the industry.”

Key factors that explain the “steady” improvement of the industry safety record include technology and equipment, relates Ballough. Efforts to push ahead with ADS-B, the sustained expansion of business jets in Part 135 service, the expansion of turboprops, and the near disappearance of reciprocating helicopters play a big role in the improved record, he says.Evidence of these factors can be found in the sharp decrease in CFIT (controlled flight into terrain) and loss-of-control in flight accidents.

Continued risks are apparent when looking at the following numbers, says Ballough: 21 percent of fatal accidents are VFR (visual flight rules) and IMC (instrument meteorological conditions); 16 percent of fatal accidents are VFR at night; 4 percent are VFR at night and IMC; and 13 percent involve issues of continued airworthiness, or maintenance. “These are areas where we can focus our future safety initiatives,” says Ballough.

The long-term story for Part 135 is good, he contends, stating, “rates and numbers are improving steadily, especially in recent years, both for accidents and fatal accidents. Fleet trends and advancing technology promise continued improvements.

Regarding NextGen, Ballough says to cynics who view the inability of the FAA to deal with the question of equippage, “What’s different today in terms of NextGen focus is that we have this stuff on paper now. Never have I seen the type of implementation plans that have been developed and followed through with like I see today.” Examples of effective implementation include ADS-B in the Gulf, and the case with UPS in Louisville, he says.

“We are doing a lot of testing out there; we are serious about this. I have not seen an effort like this regarding NextGen in my entire career in aviation,” remarks Ballough.

GA facility security

It only takes one incident to really drive policy and regulation, whether it’s reasonable or not, relates Lindsey McFarren, president of McFarren Aviation Consulting and former NATA manager of regulatory affairs.

“That’s one thing I’ll say about the Austin incident,” adds McFarren. “So far, TSA has been quick to react as far as responding to the Hill, but slow to react as far as implementing a policy or regulation; which I think is a change from what we have seen in the past.”

According to McFarren, there are three steps to developing an effective facility security program:

1) Vulnerability and threat assessment. There is an obviously different threat scenario at Van Nuys Airport than at Yoder Airport in Louisville, OH, explains McFarren. Van Nuys has fences, key card access, and a fairly controlled environment; the same is not appropriate for Yoder Field. The point is to take a hard look at the operation.

2) Gap Analysis. Take a look at what other people are doing. This can be done through NBAA’s best practices for GA security, or via TSA’s GA security guidelines, among other sources.

3) Develop and implement a security plan.

Basic security measures include employee badging, visitor sign-in, key control, and basic security training for all staff, relates McFarren. With regard to fencing and gates, “TSA will say fences are the answer; I disagree wholeheartedly,” she says. “All it would take is to back up a soccer mom’s minivan to the fence and I could be up and over in a matter of seconds. I’m not concerned that some terrorist is going to do that; frankly what I’m concerned about is that some reporter is going to do that. Gates are not the answer, controls are not the answer; it’s common sense.”

McFarren also gave a regulatory update and commended the industry on how it responded to TSA’s proposed Large Aircraft Security Program (LASP). “Industry responded in a very responsible way; there were numerous chances to go out with guns blazing against TSA — that probably would not have brought us to where we are now,” says McFarren.

“I think what we are going to see will be very different from what the proposed rule was.”

Regarding TSA’s foreign repair station security proposal requiring all Part 145 repair stations regardless of location to have a security program, McFarren says, “The program would require TSA inspections, access control, and security training.

“According to the proposed rule, TSA is able to say that a repair station poses an immediate risk to security, and it can tell FAA to revoke or suspend its certificate. There is not a very clear connection between the agencies in terms of how they will work it out; it will probably be awhile before we see a final rule.”

SMS: One operator’s experience

Key Gray, director of operations for Executive Flightways, relates that in building a safety management system (SMS) from scratch, the first step his company took was to develop an administration manual where it took every job function in the company, and listed all of the tasks involved with that job, and how those tasks are carried out. A secondary value of doing this, says Gray, is that the company came up with a good set of job descriptions, which it now uses to train staff.

“Next we developed an internal audit system,” says Gray. “This resulted in monthly audits by supervisors, quarterly audits by department heads, and trimester audits by the safety manager.” An annual audit is also conducted by the president.

“We found that it’s really important that employees know there will be no punitive action taken against honest self-reported mistakes,” remarks Gray. “It’s also important they know that their mistakes will lead only to additional testing, training, and guidance. Most importantly, they have to feel there will be some change as a result of their report.”

The hardest part of SMS, says Gray, has been safety risk assessment. “It’s the most time consuming and requires the most input from employees,” he explains.

“We have designed our system as an effort to reduce every risk to a level as low as reasonably practical. We decided that rather than senior management making the determination of what is considered reasonably practical, we tried to put the onus on the pilots and mechanics. We set up a safety review board which is comprised of at least one pilot from every aircraft group in the company, the chief pilot, the safety manager, and representatives from the maintenance side.”

That group then determines the risk level of a particular operation, listing the operational factors, technical factors, and human factors. Once the list is complete, the board does a probability and severity analysis. Then the review is passed back to senior management to determine the best mitigating factors, and back again to the safety review board.

Successes born out of the SMS include improvement in the quality of services provided, the means to anticipate safety issues and prevent their occurrence, and the means to track and correct safety issues and quality failures, says Gray.