Sacramento International Airport (SMF) is a transportation hub for Northern California handling some 30 flights by 12 airline carriers during peak hours. The airport is also located on a 6,000-acre parcel of land eight miles from the meeting of the levee-lined Sacramento and American Rivers — a region ranking at the top of the country’s most flood-prone cities. Sacramento County, taking heed of the levee failure brought on by Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans, contracted Faith Group, LLC to aid in an operations relocation plan for the possibility of catastrophic flooding.

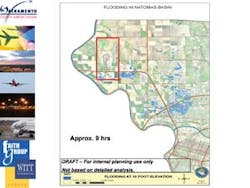

Comments Tony Bizjak of the Sacramento Bee, “Should levees fail along the nearby Sacramento and American Rivers, it would take only 12 to 18 hours for all paved roads to Sacramento International Airport to be covered by a foot of water.”

Michael La Pier, SMF operations manager echoes Bizjak’s concern, “[An] inland lake could inundate runways and airport grounds, impacting the airport to the point that it would not be able to function.”

As the state capital of California, it is critical that Sacramento have an operating airfield in the event of a major flood disaster within the Natomas Basin Levee system, relates Faith Varwig of Faith Group, a planning and consulting company based in St. Louis, MO.

The company has supplied Incident Command System (ICS)training at the Portland and Freeport International airports; disaster drill training at Cleveland Hopkins; emergency planning at T.F. Green airport; and now, a first comprehensive COOP (Continuity of Operations Plan) for SMF. The project took 18 months to complete at a cost of $324,000.

Before 9/11, relates Varwig, “You didn’t really see many airports put a specific focus on disaster management. Whatever was in the AEP (airport emergency plan) was what people went with; that is, planning for a subscribed list of events required to attain Part 139 certification, and that’s really as far as it went.

“Post-9/11 people started looking at the adequacy of those kinds of plans.”

Faith Group project manager Heidi Benaman says Hurricane Katrina in 2005 also woke everyone up. “Particularly, the city of Sacramento started to really pay attention to flood planning,” she says. “The airport, being a critical part of the state capital’s infrastructure, wanted to be proactive and have a plan.”

“[Sacramento’s] plan really encompassed completely moving operations to another off site location. I think this is the first time that’s ever been considered as part of an operations continuity plan — actually picking up operations and moving them for an extended period of time to what would be considered as a reliever facility,” explains Varwig.

“It was a fascinating project, and the great thing is all of the airlines and the third party service providers were behind the airport 100 percent.”

Designating Mather

A first step in planning was determining where SMF operations would be relocated should a major flood event occur. Mather Airport, a decommissioned U.S. Air Force Base located some 17 miles southeast of SMF, became the designated emergency commercial airport for the region.

Mather is one of four airports operated by the Sacramento County Airport System; its 70-foot elevation above sea level reduces the probability of submersion in a catastrophic flood event.

“Mather really came out to be the best choice,” remarks Benaman. “The plan we came up with was to bring in temporary structures at Mather; there is no terminal structure there, and there is a massive amount of pavement.”

Everything about the operation at Mather was going to be fairly manual, relates Benaman. No baggage systems; limited on site car rentals; and getting people to and from the airport would be a challenge because there isn’t the access and egress that is typical at a commercial airport operation.

“We had a couple different options for busing people in and out; we encouraged alternate dropoff or parking locations, making it easier to bring people in systematically from off site locations,” says Benaman.

With regard to the airfield, the ex-military runway was sufficient for commercial aircraft operation (one of the longest runways in California at 11,300 feet); and the airport provides a CAT II ILS approach and an operating contract tower.

“Mather is not a Part 139-certified airport,” relates Benaman. “Carriers would have to get the FAA to sign off on that. An airport security program would also have to be written for Mather, and TSA would have to sign off on that. Neither will sign off until an airline signs a letter of intent to operate; it would be after a disaster before a letter of intent would come … so we figured it would be at least four to six weeks, administratively, before the Mather operation could begin.

“That then gives us four to six weeks to start setting up the temporary facilities that we have planned for Mather.”

Defining the goal

“When we said we can get an airport up and operating, what does operating really mean?” asks Varwig. “What capacity; how many flights a day should we be prepared to take? Part of that we came up with internally by looking at projections of flight schedules, but we also met with the airlines.

“The first goal is defining what the real concept of operations is going to be, and then from that you start building the infrastructure and facilities you need to support that level of operation.”

The most extreme situation planned for took into account the region’s meteorological trends. Comments Benaman, “The region gets the most rain during the months of November, December, and January … which could extend into April and May when the spring snowmelt occurs. If the area flooded during this time, the airport would probably be shut down for a long time due its elevation; in a worst case scenario, SMF could be out of service for as long as twelve months.

“We started planning for the operation of one carrier. In that case, we didn’t need to invest a couple million dollars in sprung structures; we decided to use a nearby Marriott Hotel to perform all of the passenger screening and ticketing. We would secure bags and secure people and transport them from the screening location to be directly loaded onto aircraft at the airport.

“If more carriers wanted to come in, based on the throughput of the security lanes at the hotel, the airport would almost run a slot-restricted operation. Throughput of operational security would dictate the number of flights that could operate.”

TSA has verbally approved the Marriott idea — securing people and baggage to and from the airport; the plan still has to be written up, says Benaman.

Adds Varwig, “In the event that it looked like SMF was going to be out of service for an extended period of time, then option two would be implemented, which would really be the construction of a mini-terminal complex with sprung structures and temporary equipment on some vacated tarmac area.

“Basically we put together what we call a ‘grab and go’ plan, which is a series of checklists for every department so that each department would know what they were supposed to be doing. We integrated that plan to parallel the city’s flood plan, so that if the city’s flood control plan or evacuation plan was at a level one, we would also be at level one.”

Importance of communication

Stakeholders were brought in from the ground up with a kickoff meeting to start the planning, says Benaman. “Involving the stakeholders early on is really important, especially the FAA and TSA.”

Explains Varwig, “The [COOP] for Sacramento included everybody on the airport, all the tenants, all the airlines, everything. AEP’s address what the airport staff needs to be doing, but doesn’t really take into consideration all of the other tenants at the airport, and how they’re going to be handled. There is kind of a void in what the FAA requires of an airport operator in its AEP development versus what really should be required.”

Communication with the city concerning its evacuation plans for surrounding communities is also critical, relates Varwig. “FEMA (Federal Emergency Management Agency) and other agencies have designated spots — sometimes using airports, reliever airports, and adjacent properties — where deliveries or evacuations are going to take place.”

Ultimately, comments Varwig, “Our approach is in developing a cohesive concept of operations. The key to these types of operations is smooth and cohesive communications.

“If there’s a lesson to be learned from New Orleans, it’s that your phones aren’t going to work; your cell phones aren’t going to work; you’re not going to have available local Internet; and computers aren’t going to come back on right away.

“Developing a very good communications plan, and then exercising that plan is key. Putting a plan on a shelf doesn’t do any good; it has to be looked at and exercised on a regular basis several times a year.”

This kind of comprehensive planning project, remarks Varwig, is an undertaking; it’s not inexpensive and it’s very manpower intensive.

Looking forward, Benaman says Faith Group hasn’t been contracted to do this yet, “But we’ve encouraged the airport to plan for coming back to Sacramento International. How to demobilize the Mather operation and start back up at Sacramento — that’s another operational planner in and of itself.

About the Author