Mitigate Airport Security Risk Via Contractor Vetting

Every day, millions of people head to airports around the globe. Some are going on dream vacations. Some are making moves across the country. Some are simply commuting for another day in the office.

As they head through security lines, these travelers have a lot on their minds. Am I going to make it on time? Did I pack everything I need? Will I be able to get my coffee before I board the plane?

While safety is often a concern, when passengers decide to travel by air, they’re entrusting their lives and the lives of their loved ones to airline officials and airport employees who they assume are working to mitigate potential security risks at all times.

Though obvious aspects of ensuring airport security – such as passenger identification measures and adequate screening of people and personal property before boarding flights – are widely discussed among airport professionals and laypersons alike, one area that is often overlooked is potential security threats posed by airport contractors.

From facilities custodians to airplane mechanics to pilots, nearly one million contractors work behind the security wall at U.S. airports alone, according to CNN. And while security has significantly strengthened since 9/11, a New York Committee for Occupational Safety & Health (NYCOSH) report shows better supply chain risk management via stricter contractor screening procedures could have helped identify situations therefore potentially preventing a number of deaths and injuries at major airports in recent years.

So, what are the leading known, manageable risks associated with airport operations that are most frequently overlooked? And how can airports improve the contractor vetting process to mitigate the likelihood of behind-the-scenes safety and security issues that many passengers aren’t even aware of?

Everyday tasks

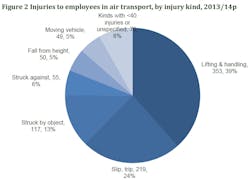

According to a Health and Safety Executive (HSE) study that examined accidents and dangerous occurrences in the air transport industry over a four year period, improper lifting and handling is the top cause of employee injury, accounting for a notable 39 percent of the report’s total anonymized and aggregated data.

Despite the commonness and predictability of the activity, baggage lifting, in particular, results in significant muscular skeletal injury rates due to the ergonomics associated with handling heavy weight and the particulars of the position and height of the lift that’s required, especially if done repetitively. The risk of injury also rises when performed in confined spaces in the cargo hold or amongst passengers in the cabin by ground staff and cabin crew.

Per the pie chart at the top of this article, accidental slips and trips followed as the second most common injury type behind lifting and handling, accounting for 24 percent of total injuries. Being struck by an object ranked as the third highest reoccurring injury with 13 percent of the total.

Although not included in this chart, work stress is another potential risk airport contractors and their employees are exposed to daily. As with any job, harmful physical and emotional responses can occur when the requirement of the job does not match the capabilities, resources or needs of the worker.

Exposure to unsafe elements

Apart from these everyday tasks that are inevitably a part of the job description, NYCOSH’s survey (cited above) of workers employed by some of the largest airline contractors operating at John F. Kennedy (JFK) and LaGuardia (LGA) Airports reported hazardous materials, extreme weather and unsafe noise volumes as some of the harshest and potentially dangerous elements they are exposed to during the course of their workday.

If unaware of the chemicals in the cleaning and disinfecting products they are using, workers run the risk of suffering eye, skin and respiratory infections from inappropriate contact. Misuse can put passengers at risk as well, as too minimal use, or no cleaning product use at all, can create unsanitary conditions that are breeding grounds for disease. Too much cleaning product can cause overwhelming fumes, putting pilots, crew and passengers at risk.

As worker’s clean cabins, wheelchairs, terminals and more, they are also frequently exposed to blood and other bodily fluids, such as vomit and urine, posing the risk of coming into contact with blood borne pathogens that can transfer disease to humans.

Aside from these apparent chemical and biological risks, those working day-in and day-out on the tarmac are regularly exposed to fuel emissions and carbon dioxide coming from engines in jets, vehicles and equipment. While low levels of exposure can cause headaches, lightheadedness, fatigue, impaired judgment, motor skill deterioration and loss of consciousness, high levels of exposure can lead to extremely severe side effects, such as cancer and death by suffocation.

Although most people are aware excessive amount of exposure to CO2 has scientifically been proven to cause health problems, a natural element that isn’t always initially thought of as life-threatening is weather. However, excessive exposure to extreme heat can lead to heat rash, heat cramps, heat exhaustion and even heat stroke, while prolonged exposure to freezing or cold temperatures may cause serious health problems, such as frostbite and hypothermia.

The final hazard discussed in NYCOSH’s report was exposure to extreme noise levels from airplane engines, which can cause permanent hearing loss that cannot be surgically corrected or improved with hearing aids. Exposure to loud noise can also cause psychological and physical stress and hypertension, reduce productivity, interfere with communication and concentration and contribute to workplace accidents and injuries by making it difficult to hear warning signals.

The areas of airport operations most likely to increase operational risk include but are not limited to:

- Airside Driver and Vehicle Operations –including safety policies, such as distance between vehicles, speed in designated areas and number of vehicles and drivers present in loading areas.

- Apron Management – managing aircraft parking, loading/unloading and fueling and boarding areas.

- Biological – including aircraft waste storage and disposal (blood borne pathogens).

- Construction and Maintenance – ensuring infrastructure is properly maintained and construction areas are appropriately marked and blocked during maintenance periods.

- FOD (Foreign Object Debris) Management – including any objects found in an inappropriate location that – as a result of being in that location – can damage equipment.

- Ground Handling Operations – defining the servicing of an aircraft while it is on the ground and usually parked at a terminal gate of an airport.

- Hazardous Material Handling – including oil or other petroleum products, solid waste and any other toxic substances.

- Markings, Signs and Lighting – including identification/notification of areas where an aircraft is to hold before entering a runway, where a runway or taxiway is closed and other important notices for entering and exiting runway and terminal areas.

- Movement Area Access Aerodrome Works – permitting access onto the movement area to authorized personnel and vehicles.

- Movement Area Maintenance – maintaining the runways, taxiways and other areas of the airport that aircrafts use for taxing.

- Movement of Aircraft – including ensuring proper coordination with other aircrafts on runways, taxiways and other areas of the airport used for taxing.

- Obstacle Management – including defining, assessing, controlling and removing the obstacles in the vicinity of the area in which flight operations occur.

- Rescue and Firefighting – a special category of firefighting that involves the response, hazard mitigation evacuation and possible rescue of passengers and crew of an aircraft involved (typically) in an airport ground emergency.

- Runway Operations – including ensuring coordinated landing and takeoff of aircrafts.

- Winter Operations – planning and implementing safety policies and procedures around snow, ice and slippery weather conditions.

Improving safety and security

When time literally means money, the urgency for airports to keep their flights coming in and going out puts heavy pressure on employees to move as quickly as possible, potentially not allowing much room for reflection on safety standards. That is, until the airline receives a massive Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) fine for violating federal requirements.

The haste associated with airplane turnaround times is often the cause of employee injury or death. In some cases, engineering controls can be put in place from a health and safety perspective to eliminate boots-on-the-ground hazards completely. However, each and every known risk could be properly managed through structured risk assessment and risk management practices that have been well-documented for airports through risk registers, such as TRB’s Airport Corporative Research Program (ACRP) Safety Management Systems for Airports Guidebook Volume 2 and Airports Council International (ACI) Safety Management Systems Handbook.

Risks are systematically identified and risk control measures documented in such risk registers that define how each risk will be managed. The operational controls are generally formally captured in procedures that are incorporated into the airport’s safety management system. For example, ACI’s APEX program provides for auditing and benchmarking of the airports effectiveness by implementing an appropriate safety management system to manage safety risks.

Ensuring that all hazards are recognized and reinforced with education campaigns is imperative to preventing disaster. It should not be assumed that the employees engaged have requisite skills until they are vetted and operational safety procedures have been properly communicated before they undertake the work.

Contractor vetting

Contractors have proscribed activity-dependent procedures that must be followed at all times to ensure the safety of everyone involved. For example, an airport contractor has lifting, working at height and airside vehicle operational procedures and training programs for its employees. If a contractor has not developed appropriate procedures for driving operations airside and ensuring they have processes to train their employees, there is a real risk of vehicle incident potentially impacting the airframe or other vehicles.

Likewise, there are significant working at height risks associated with a number of activities with ground handling and operations. Therefore, it is critical that the contractors are screened to ensure that they understand the risks and appropriate controls are developed.

The management of these risks has increased in complexity with the utilization of contractors to undertake ground support activities traditionally undertaken by the airlines. There is a growing need to prequalify the contractors to ensure that they have appropriately understood the risks associated with their services and that they have the appropriate controls in place to mitigate the likelihood of accidents.

Given the potential consequences associated with airside risks, in particular, it is critical that contractors are screened to ensure that they understand the risks that they are exposed to when they are airside. When inadequately addressed, these risks can significantly disrupt business, potentially impacting specific flights, airlines and airport operations.

The impact from one event can easily extend beyond the contractor. For example, if during a construction project a contractor’s employee accidently severs a major fiber optic cable at an airport just as it is coming into a peak traffic period, the airport would likely need to shut down for 90 minutes or more and redirect airplanes to other airports, until airport officials are able to bring the systems back on line.

The repercussions of this civil construction contractor not operating within appropriate ground disturbance procedures, resulting in the severing of the cable, would be significant to passengers, airlines and the operation of the airports. This event could have been prevented if the contractor had been screened and their ground disturbance procedure and training reviewed prior to being awarded the contract. And, while this was a serious event, resulting in inconvenience for airline passengers and personnel in multiple locations as well as financial loss and reputational impact, it could have been far worse –contractor errors and inadequate contractor vetting can – and often do – result in more serious harm, including death.

Continually monitoring contractors and their employees to ensure they maintain airline, airport and industry best-practices promises to help close the gaps, resulting in fewer injuries therefore a safer environment for all, improved efficiency and reduced costs.

Mina Mina, ASP is senior director of client success for Avetta. He brings more than 15 years of dedicated health & safety professional experience, specializing in audits, commercial insurance and regulatory compliance and consultation based on jurisdictional requirements. Mina earned his Bachelors of Arts degree in Criminal Justice/Law from California State University, Fullerton. He also holds an ASP Certification through the BCSP (Bureau of Certified Safety Professionals) as well as other certifications relevant to the health & safety space.

About the Author